Having trouble detaching from work? It might be time to think about how you recover

In the sporting world, the term ‘recovery’ is widely used to describe the physical recovery from the sport itself. That traditionally may take the form of active or passive rest, massage, ice baths, physiotherapy and more. But the idea is that if you’re a professional athlete, you spend time recovering from your endeavours so that your body is ready to go again when the time arrives.

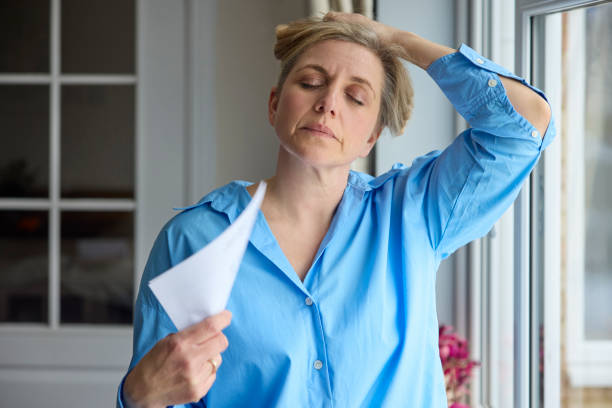

The same philosophy can apply to working life. Yet, in practice, many of us do little to actively ‘recover’ from our working day. And yet, when we don’t, the ability to detach from work is diminished, our sleep is compromised, our on-the-job performance dips and our mental health and wellbeing suffers.

So, how do we recover from work?

Professor of Work and Sports Psychology and leading expert in employee sustainable performance Dr Jan de Jonge, says that “detachment from work should encompass cognitive, emotional and physical absence from work.” In other words, you need to be able to disconnect the mind, the soul, and the body from your work.

Generally speaking, de Jonge says, the best approach is to engage in a recovery activity that is a ‘mirror’ of your work.

“For instance, an employee whose job requires high emotional effort would be better off avoiding engagement in recovery activities that put high demands on the same (i.e. emotional) systems,” de Jonge says.

“Similarly, a construction worker with a highly demanding physical job would be better off avoiding engagement in recovery activities that put high demands on the same (i.e. physical) systems.”

What does this look like in practice? Simply put, if your job uses physical energies, you may find you recover better when you spend your out-of-work time engaging in more cerebral activities, like reading, watching television or social interactions.

Similarly, if your job involves sitting at a screen all day, you may find that engaging in a more physical activity, like going for a run or gardening, might help you switch off.

The role of joy in recovery

Joy, de Jonge acknowledges, plays a critical role in recovery as well (for employees and for athletes).

“Our research shows that pleasure in recovery activities is more important than the type of activity,” de Jonge says.

“People should spend recovery time on activities that they like most.”

That means if you spend all your work time at a screen, but you get true joy from watching arthouse cinema, you shouldn’t let what you did all day stop you sitting down to a film – as that joy may be just what you need to best detach from your work.

It also means that while doing something like reading may be beneficial to a physical worker, if it’s not something you enjoy, it’s probably worth thinking about a different joyful non-physical activity to help you detach.

How long do you need to dedicate to recovery to truly detach?

“It’s important to explore recovery opportunities during and after working hours,” de Jonge says, suggesting that 5-10 minutes of rest can be quite effective when used as actual ‘recovery’ time. Regular breaks throughout the working day can go a long way to supporting recovery and reducing work stress.

For example, de Jonge suggests that if you are engaged in heavy or tiring work, taking a structural break every hour for up to five minutes is very beneficial. Even toilet breaks can be considered micro breaks, and a chance for a small reset. Research also shows that employees who took micro breaks had an energy and mood boost that translated into better performance.

One of the factors seriously impeding our ability to recover from work stress is what is often termed our ‘new way of working’.

“Working flexibility, along with IT development, has increased more and more over the past few years,” de Jonge says.

This new-found flexibility, he acknowledges, can enable boundary-less working hours, which implies less recovery time and keeping people mentally occupied with work during non-working time.

Yet, de Jonge adds, “research shows that fully detaching from work after work is most effective”. This, he concludes, can be because complete detachment during work hours is often more difficult , given interactions with colleagues and work can still occur.

Moreover, research indicates that psychological detachment in the evening positively predicts next-day job performance via higher sleep quantity. And a higher state of being recovered in the morning promotes daily work engagement and daily job performance, including task performance and personal initiative.

How do we turn off amid ‘always on’ technology?

For those who don’t have a physical space to distance themselves from, the act of switching off for recovery can be more difficult.

Being intentional about managing technology, de Jonge suggests, can go a long way to supporting recovery. For example, you may want to consider:

- Turning off email and smartphone alerts

- Only checking email at fixed times of day (e.g. at the end of the morning)

- Addressing emails directly, and then moving them out of the inbox

- Filtering news items, and blocking irrelevant emails from contributing to your ‘inbox burden’

- Efficiently using out-of-office answers – de Jonge suggests being clear on when you’re not available, and when you’re not answering emails in your time off

- Not checking email or work phones on the weekends or holidays

- Not having your work email on your (private) smartphone

- Not using your phone during meetings.

What can leaders do to support recovery?

“Managers and organisations play an important role in on-job and off-job recovery,” de Jonge says.

“They should create a work climate in which working beyond regular work hours is not ‘business as usual’” he says, again acknowledging that this ‘always on’ approach can seriously impede recovery and sleep processes, and ultimately impact job performance.

Managers, de Jonge adds, have an important role to play in modelling recovery.

“Managers should act as role models by not being available during non-work time and should not contact their employees during this time as well (e.g. via phone, email etc),” he says.

Ultimately, they need to be doing what they can to actively encourage their employees to include recovery activities in their working and private lives for the benefit of their mental health and wellbeing.

Finally, de Jonge acknowledges, it’s important to remember that there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to work stress recovery.

“Different employees need different times for recovery, and benefit from different types of recovery activities. What characterises successful recovery periods and activities is that they enable and are accompanied by specific psychological experiences and internal states.”

Ultimately, he suggests spending recovery time on activities you enjoy the most can be the best first step to detaching and reducing work stress.

Want to learn more? Unpack recovery further and learn practical strategies to help protect your mental health and wellbeing in three related workshops: When switching off is the goal: How to relax and detach from work; Health reset: Making healthy habits part of routine; and Setting boundaries: Drawing a line between work and home.