A Trauma-Informed Approach to Protecting Employee Wellbeing

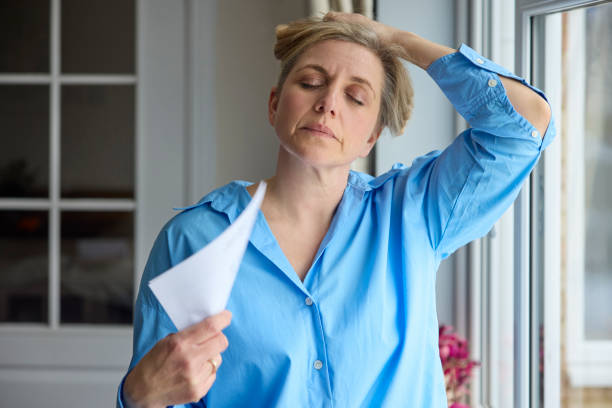

Across Australia’s customer service industry, an alarming 87% of frontline staff have reported experiencing verbal abuse in the past year alone.

With customer aggression peaking around busy shopping periods like Christmas and Easter, we’re seeing a concerning trend at the coalface: the traditional ‘customer is always right’ mantra is taking a toll on employee mental health.

The current landscape

A recent survey of more than 4600 retail workers reported 87% of workers experienced verbal abuse from a customer, 12.5% reported physical violence, and 52% said the same customer acted abusively or violently on more than one occasion (Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees Association, 2023)

These statistics aren’t just numbers – they represent real trauma experienced by frontline workers.

Why customer aggression is rising

The escalation in customer aggression reflects a perfect storm of societal pressures and systemic changes. At its core, rising inflation and cost of living pressures are creating a baseline of financial anxiety that often manifests as decreased emotional regulation.

This financial stress is compounded by the lingering effects of the pandemic, which has fundamentally altered how we interact with each other. The collective trauma of recent years has depleted our ‘surge capacity’ – our ability to adapt to stressful situations. Throw our modern digital lives into the mix with social media normalising confrontational behaviour and instant gratification, and we’ve developed unreasonable expectations for service timeframes.

The service industry faces its own perfect storm of technological change, compliance issues, staff shortages, reduced training time, and high turnover rates. Fewer experienced staff handling increasingly complex situations, alongside longer wait times and service inconsistencies, creates a volatile environment where customer frustrations can quickly escalate.

Understanding trauma in customer service

Many organisations fail to recognise that repeated exposure to customer aggression can constitute trauma. As highlighted by SAMHSA (2014), trauma results from “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful… and has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning.”

This definition is particularly relevant when considering that the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2022) reports 75% of Australian adults have already experienced a traumatic event in their life. Customer service workers may therefore be managing both previous trauma and ongoing exposure to aggressive interactions.

How can organisations create a supportive environment for traumatised employees and leaders?

“Recognise that trauma is unique to the individual who experiences it,” says Transitioning Well’s Vanessa Miles. “Two people can experience the same traumatic event – one might experience what we could call ‘appropriate distress’ while the other might develop a traumatic response. There are factors that influence different responses. One important consideration to be aware of is that social support is protective when people have these experiences.”

It can also be helpful to do a risk assessment says Vanessa. Think about where in your workplace is there the potential for trauma to occur. This may be obvious in some settings – eg. ambulance. But for example a vet , one might assume it’s euthanasia that is distressing. This can be true, but human interactions, for example when a person can’t afford lifesaving treatment for their pet – that’s another source of distress.

So organisations can ensure they are well equipped to link their people to appropriate support when a distressing event occurs.

A three-tiered approach to protection

1. The leadership layer

Leaders must be educated about trauma-informed practices to:

- Recognise signs of trauma exposure in their teams

- Understand that trauma affects people differently

- Create psychologically safe environments where employees feel supported

- Implement proper reporting and response protocols for aggressive incidents

2. The customer layer

Organisations need robust systems to:

- Set clear boundaries with customers about acceptable behaviour

- Empower employees to disengage from threatening situations

- Provide de-escalation training

- Create physical environments that prioritise employee safety

3. The self-care layer

Employees need support to:

- Recognise their own stress reactions

- Understand that stress responses (fight, flight, freeze, or fawn) are normal reactions to abnormal situations

- Access appropriate mental health resources

- Develop personal resilience strategies

Implementing trauma-informed practices

A trauma-informed workplace acknowledges that:

- Each person is doing the best they can with the resources they have

- Stress reactions manifest across emotional, physical, and cognitive domains

- Support needs to be stepped up when distress persists beyond a month

- Re-traumatisation must be limited wherever possible

Moving forward

The rise in customer aggression is a significant workplace health and safety concern that requires a trauma-informed response. By understanding that trauma affects people differently and implementing comprehensive support systems, organisations can better protect their employees’ mental health and wellbeing.

It’s important to note that while experiences of traumatic events are common, with proper support and protective factors in place, most people don’t develop ongoing mental health conditions. The role of organisational leaders is to ensure that those protective factors are robust and accessible.

The investment in trauma-informed practices isn’t just about meeting duty of care obligations or, in other words, ticking a box. Mentally healthy workplaces allow people to bring their whole selves and be valued for who they are, even in the face of increasing customer aggression.

To find out more about how Transitioning Well can help your organisation, see our Learning Catalogue.