Burnout: Why Workplace Exhaustion Persists in 2025

Updated March 2025

Original article by Leah Ruppanner, The University of Melbourne; Brendan Churchill, The University of Melbourne, and David Bissell, The University of Melbourne

While the “great resignation” dominated headlines in the US during 2021-2022, Australia experienced a different workplace phenomenon. Rather than mass resignations, Australian workers faced what experts called the “great burnout” – a widespread condition of exhaustion and disengagement that continues to affect the workforce today.

The Great Burnout: Then and Now

A landmark 2022 study of 1,400 employed Australians revealed trends that have shaped our current workplace landscape:

- 50% of prime-aged workers (25-55) reported feeling exhausted at work

- 40% experienced decreased motivation compared to pre-pandemic levels

- 33% found it harder to concentrate due to responsibilities outside work

- One-third were actively considering quitting their jobs

These statistics represented the “quiet quitters” – employees who remained in their positions but experienced significant burnout. Three years later, research shows these challenges persist, indicating burnout rates haven’t gotten better despite workplace adaptions.

A recent study highlights just how much burnout and unmanaged workplace stress is affecting people:

- Nearly 40% of Australian workers expect stress levels and burnout to be harder to manage in 2025 compared to the previous year, while only 20% believe it will improve.

- Two in five employees are beginning the year already burnt out.

- 90% of Australian workers feel that burnout is ignored until it becomes critical. Over half say the warning signs are identified too late, while 39% believe they are outright ignored.

- More than half of Australian workers would take burnout leave if it were available. However, workplace culture remains a barrier: 8% fear being judged for taking burnout leave, and 7% say their workplace simply would not allow it.

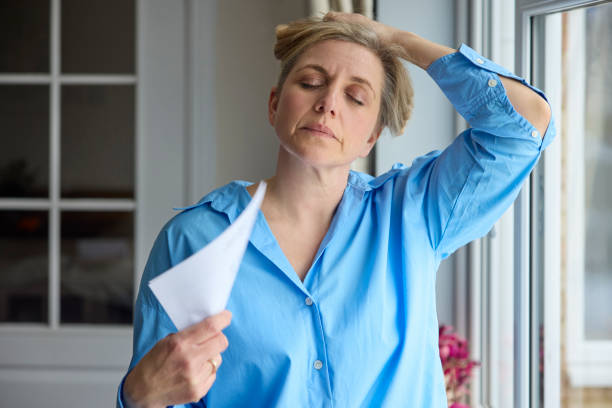

The signs of burnout can include:

- feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion

- changed sleep patterns

- loss of appetite

- irritability

- brain fog and reduced professional efficacy

- disinterest or a lack of participation in work or activities that you previously enjoyed

- feelings of negativity and cynicism related to your job

- a general feeling of detachment.

Why Aussie Workers Continue to Burn Out

The COVID pandemic triggered unprecedented disruptions to working life, but even as pandemic restrictions have disappeared, burnout factors remain:

- Lingering trauma: Many workers never fully recovered from pandemic-related stress

- Increased workloads: Staff shortages in key industries have led to heavier responsibilities

- Economic pressure: Rising living costs and inflation have created additional stress that affects workplace performance

- Digital overload: Remote and hybrid work arrangements have blurred boundaries between personal and professional life

Women and caregivers continue to face disproportionate challenges. Industries with high female representation – healthcare, education, and social services – report the highest ongoing burnout rates in Australia.

Flexible Work: The Proven Solution

Despite the emerging political debate around flexible work—with the opposition leader recently stating a Coalition government would require public servants to work from the office five days a week—the evidence supporting flexibility remains compelling.

- Flexible workers reported higher energy levels and motivation

- 40% of flexible workers felt more productive compared to 30% of non-flexible workers

- 75% of workers under 54 said lack of flexibility would motivate them to seek new employment

This data contradicts the narrative that in-office work universally improves productivity. Global workplace research continues to suggest that flexible arrangements can positively impact:

- Employee retention and loyalty

- Overall productivity and efficiency

- Workplace satisfaction and wellbeing

- Reduced symptoms of burnout and stress

What solutions help reduce workplace burnout?

The research identified flexible work arrangements as the most effective solution for reducing burnout among Australian workers. As organisations plan for the future, two critical insights remain relevant:

- The workforce remains vulnerable to burnout. Acknowledging this reality and implementing targeted support systems is essential for maintaining productivity and retention.

- Pre-pandemic work models were inherently flawed for many. They disadvantaged parents, caregivers, people with chronic illnesses, and those with long commutes. Creating new, more inclusive work arrangements is not a bonus but necessary.

Effective strategies include:

- Workload management: Setting realistic expectations and proper resourcing

- Support programs: Offering meaningful mental health support beyond token initiatives

- Skills development: Providing training to help employees manage stress and set boundaries

- Leadership training: Equipping managers to recognise and address burnout symptoms

Other potential solutions include acknowledging the ongoing impacts of workplace trauma, creating more inclusive work environments, addressing the specific needs of caregivers, and developing sustainable work models that don’t disadvantage vulnerable groups.

The Future of Work in Australia

“It’s important for all business leaders to be on board with mental health policies and practices, communicating them effectively with their people and ensuring that they are also looking after themselves and walking the talk. Now more than ever it is important that leaders are well so that they can lead well,” says Transitioning Well co-founder, Dr. Sarah Cotton.

Rather than thinking (like politicians) ‘when will we return to normal?’ the conversation is shifting to ‘how do we create better working environments that prevent burnout in the first place?'”

For workers and employers, the answer increasingly involves reimagining workplace structures to prioritise wellbeing alongside productivity – creating sustainable models that can withstand future challenges.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.